Everything around us is magic, and nobody knows how things work. From the phones in our pockets, to the cars that ferry us around, to our systems of government, all of the critical things that have changed the way we think, work, and play are black boxes to many of us.

Systems have become complex and hard to navigate. As a result, we tend not to scratch below the surface, but instead work on top of them. As systems around us continue to become more complex, it’s more important than ever to understand how they work. This is for one simple reason: if you don’t understand how a system works, then you can’t truly participate in it, and its development. This turns us into passive bystanders, both in life, and through the things that we utilize on a daily basis. Without this understanding, the few who do comprehend how a system works can easily abuse it to their own advantage.

To address this problem, we’ve come up with useful constructs like systems thinking to help us deconstruct and understand what’s happening around us. Systems thinking gives an individual insight into the system they’re engaging with in order to best take advantage of its components toward achieving an ends. However, systems thinking only advocates for an understanding of a system in order to leverage its components. But what if the components are broken? Extraneous? How do we determine if the components in a system, or the system itself, is worthy at all?

At several of the companies I’ve recently worked with, we see this problem highlighted in their culture of “innovation.” Engineers are often tasked with taking a pre-existing thing, and are told to focus on improving that thing by 5-10% every year. They understand the components that they’re working with, and how to leverage those components in the system to register higher yield, but haven’t been given the correct context to take it any further than that.

But what if a company, or a entire field, is experiencing disruptive change? What if, instead of requiring a 5-10% change, we require an entire shift?

The problem is that innovating by making things 5-10% better does not require an understanding of the systems that underlie the things we’re improving on, only a knowledge of the general taxonomy of the system one is working within.

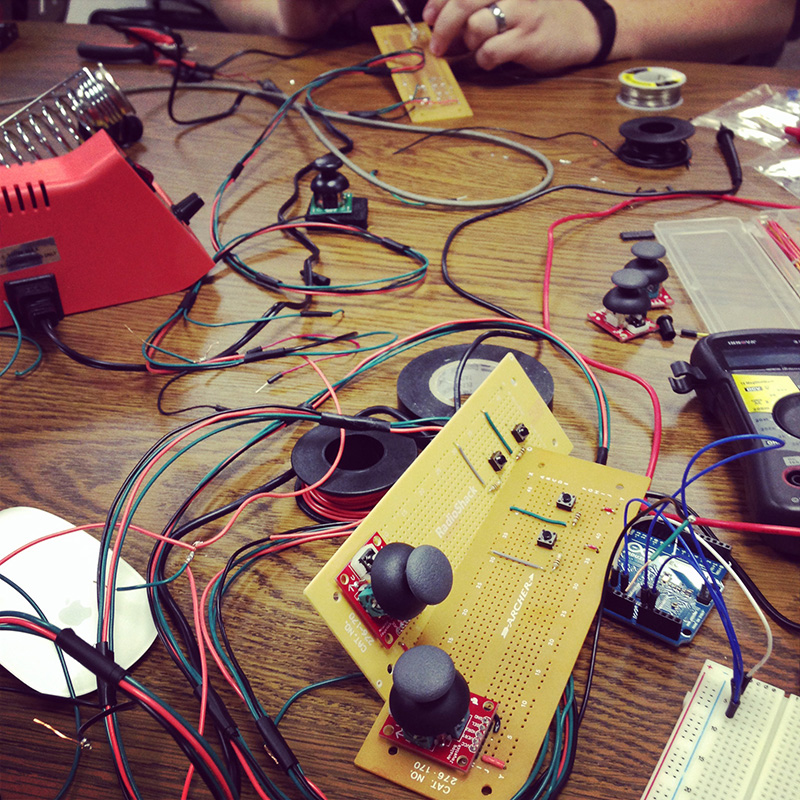

In order to truly understand a system, then, we must go a step further than being able to describe its model; we need to engage with it. I propose, moreover, that any meaningful engagement with a system must come from playing with its components: taking them apart, tinkering with them, and putting them back together.

In “Making: Anthropology, archaeology, art and architecture,” Tim Ingold talks about how, when we engage with the physical, we are able to escape many of the preconceptions in our minds as we think. That’s because physical materials push back against those preconceptions: the real world has a way of doing that. Making explores this intersection of thinking through tinkering. More than that, making enables one to explore systems through tinkering.

Take an example I recently heard from a student, who, when describing the 3D printing of an object for a vehicle they were working on, said: “as I watched it print out, I already had another idea for the next iteration of the thing.” They could see the object on the screen before printing it, but seeing it in the physical, and being able to move beyond the conceptual phase, spurred new ideas.

The creation of components and active engagement in systems, I think, is vital to our understanding of those things. Theorizing and analyzing is not enough, as it leaves us with our own preconceptions and biases, and does not allow us to be truly critical of the system that we’re analyzing. In order to give us the capability to question a system, or the components in a system, one must engage with it in a playful, active disposition.

Moreover, understanding systems by engaging with them is important to a future where we can question the things we consume and the systems that we engage with. It makes us active participants in an economy of ideas and creation, rather than passive consumers. By tinkering, we are able to reveal knowledge that was beforehand opaque. We’re able to question.