Developing real, tangible things is a messy process where one must listen to, and work with, the material they have available to them. By allowing the materials to lead the process of development, we embed their imperfections and constraints into our designs, which subsequently influences how we interact with the creation. In other words, the materials in the product inform the experience of the end-product.

This has some interesting implications. In the electrical outlet, material considerations lead to the quirks we know today, and that influence millions of devices that require electrical power. In the development of game badges that I’ve written about, the material (antennae, screens, etc) ultimately influences the kinds of interactions that the games on the platform encourage. And in the documentary 808, another case of material informing object is made when, toward the end, Ikutaro Kakehashi, the engineer behind the 808 and the founder of Roland Corporation, describes the development process behind the Roland TR-808.

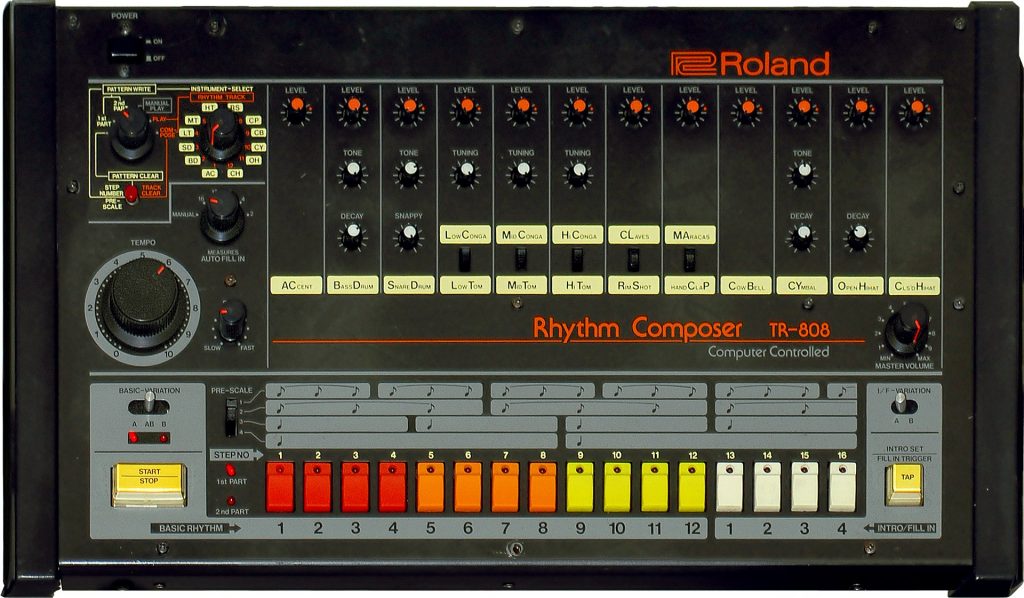

The TR-808 came out of both Kakehashi’s desire to make an instrument, and Roland Corporation’s inability to compete with larger instrument-making companies like Steinway and Yamaha. So instead of competing on equal ground, Kakehashi created a new kind of instrument: the 808, a kind of programmable board that could output instrument-like sounds.

Because of the limitations in electronics at the time, the 808 could only simulate the sounds of a drum. As obvious as it may seem now, this first limitation led to the creation of a new sound that we now associate with hip hop and the many other musical genres influenced by the 808. This is the first way that materials influenced the creation of the 808, but perhaps not the most interesting one.

As Kakehashi further explains, in order to create the signature sizzling sound that the 808 is known for he bulk-purchased defective transistors that would have otherwise been thrown in the trash heap. Since the production of transistors had not been perfected yet, about 2-3% of those created came with defects that made them unusable for traditional purposes, but perfect for the sound he needed to generate for the 808. Soon after, the development of transistors was further perfected, eliminating the defective components that gave the 808 its sound and consequently eliminating the production of the instrument. The very origin of the 808’s sound led to its demise.

We don’t often ask questions about the origins of a platform or a system even though it may strongly influence the designed experience (this is something that’s explored quite well in platform studies, however). Yet, something like a defective component produced in a manufacturing process has the potential to influence the development of an instrument, which in turn influences the music made with that instrument platform. Even more, that very component had so much influence over the instrument that it led to its own demise. Material is inextricably tied to platform.

If, then, materials have so much influence over platforms, and platforms have influence over the creations made on them, we should pay close attention to those fundamental building blocks. By understanding them, we understand the decision-making process behind the development of the platform, and can begin to ask new questions about it. Why were these decisions made? Are the constraints that informed the decisions still necessary, or are they extraneous?

Asking questions like these is where we can begin to deconstruct a system, and ultimately, to move beyond its limitations to create something new.